February | Black Architects and Builders

Many of the historic buildings we revere in North Carolina are credited to their owners. Rarely are the people responsible for the labor and craftsmanship recognized. Preservation North Carolina’s We Built This exhibit was created to help acknowledge the countless African Americans who built the historic buildings we collectively treasure. These individuals were skilled in principles of engineering, construction, and business. Many became political and social leaders in their communities.

The profiles and stories included in our exhibit are just a few that begin to tell a more complete history of the Black artisans who built North Carolina. Acknowledging the significance of this history is a start to preserving a tangible link to the past through our built environment. This month, our America 250 Across NC posts will feature PNC-protected properties that are highlighted in our We Built This exhibit.

African and English traditions combined to influence NC’s early buildings. Traditional African building practices produced highly skilled woodcarvers, brickmakers, brickmasons, and blacksmiths. Enslaved Black artisans worked in every building trade: sawyers, carpenters, joiners, plasterers, house movers, stonemasons, bricklayers, and painters. Some learned their trades informally from other enslaved artisans. Many were apprenticed to Black or white master craftsmen by their enslavers who hoped to increase their value for sale or hire.

In 1860, approximately eight percent of the state’s Black population was free. To be free, one’s mother had to be free at the time of birth, regardless of who the father was. Freedom could also be purchased or granted, although state law severely limited emancipation. Free Black men often worked in the building trades. Apprenticeship laws encouraged trades training for free Black children.

Following the Civil War, many of North Carolina’s Black builders became the first formal political representatives of the African American community. The skills and education they had developed as enslaved craftsmen helped them rise as leaders.

Despite the limitations imposed by segregation and a loss of human and voting rights, some Black builders thrived as entrepreneurs and helped develop businesses that served Black communities. They created insurance companies, banks, funeral parlors, barber shops, hospitals, and other businesses exclusively for Black clientele. Black business districts formed in many cities, sometimes with a Masonic Lodge at the center.

Preservation North Carolina’s We Built This program is composed of three parts. A detailed and illustrated traveling exhibit, “We Built This: Profiles of Black Architects and Builders in North Carolina” is currently on display at North Carolina Central University in Durham. A televised documentary is in the final stages of completion; and a third component of the program is a book that will be published with UNC Press next year. Click to learn more about how to bring the We Built This exhibit to your community!

Lewis Freeman House, Pittsboro

The Lewis Freeman House in Pittsboro, Chatham County, was built by a free Black man, Lewis Freeman, between 1811 and 1837. This modest dwelling began as a one-room structure, a typical house form across our state in the nineteenth century. The timber frame cottage was a step up from a log house and was heated by one exterior end chimney. The house contained a small second-story loft reached by a ladder or boxed-in staircase. An early one-room addition with a slightly lower roofline was added to the west side of the house. It features a notable chimney that has a stone and clay base that supports a narrow brick “neck.” Another addition was added in the 1890s that included a front porch with turned posts, and a sawn pendant border and foliated brackets.

The Freeman family has a complicated and interesting history. Lewis Freeman was memorable not only due to his free status, but also because he owned more than 20 acres of land. His son, Waller, was a carpenter born in 1800 to Lewis and a woman named Maria who was enslaved by Charles J. Williams of Chatham County. Although Lewis and Maria lived “in the manner of husband and wife,” Waller was born enslaved because of his mother’s status. Sometime after Waller’s birth, Lewis purchased Maria from Williams. At the time, emancipated slaves were required to leave the state so Lewis never legally freed her.

Waller was purchased in 1829 for $388 by Judge George E. Badger of Raleigh. While enslaved by Judge Badger, Waller started his own family before being purchased by his father several years later. Waller remained enslaved by his father so that he could live in North Carolina.

After his mother’s death, Waller was sold by his father to a white Raleigh lawyer who took him to New York to emancipate him. However, state law would not allow Waller to return to the state to live as a free man. He risked this and returned to Raleigh, attempting to purchase his own wife and six children from Judge Badger. Waller was forced to leave the state in 1840.

That same year, Judge Badger was appointed as Secretary of the Navy under President William Henry Harrison, an appointment that required him to move to Washington D.C. He took Waller’s family to D.C. with him. Waller followed his family and purchased them for $1000 from Badger. The Freeman family remained in D.C. where Waller had a successful career as a carpenter. He died in 1868. Waller’s son, Robert Tanner Freeman, was in the first class of Harvard Dental School and became the first licensed African American dentist in the country.

PNC covenants to protect the Freeman House were recorded in 2000. The house has been carefully preserved and serves as the office of Hobbs Architects. Learn more here.

Union Tavern, Milton (and other Thomas Day properties)

Thomas Day was a free man of color, a furniture maker, and woodworker who owned the largest cabinet shop in the state during his time. He maintained a successful business for nearly 30 years during which he is credited with producing architectural interiors for homes, churches, and public buildings in North Carolina and Virginia. His designs were often highly individualized adaptations of the latest styles.

Day was born to free Black parents in Virginia and apprenticed under his father, also a cabinet maker. He moved to Milton in Caswell County in the 1820s and established a successful cabinet-making business. His work became highly coveted among the white elite.

Day attained a degree of respect, prosperity, and freedom that was rare for people of color. According to tradition, Day’s shop built and donated church pews for the Milton Presbyterian Church, the church he attended. Milton’s white citizens supported an 1830 legislative petition to allow his wife to move to North Carolina from Virginia. At the time, free Black people were not allowed to move into the state.

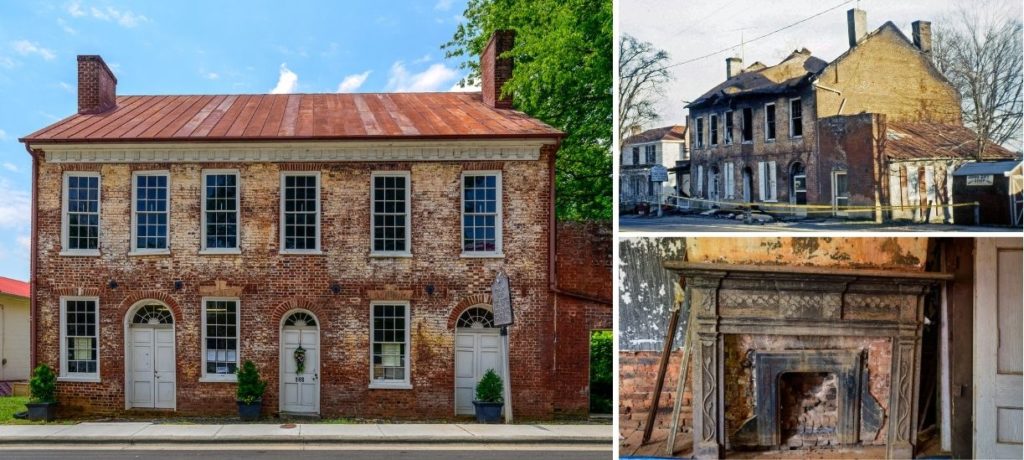

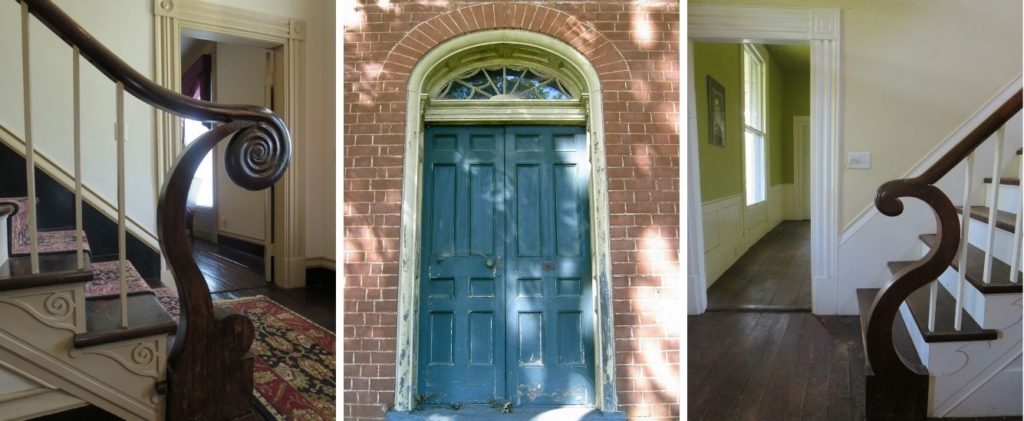

In 1848, Day purchased the Union Tavern in the town of Milton near the Virginia border. The building served as his family’s home and his woodworking shop. He trained white and Black apprentices and owned enslaved workers. The ca. 1818 tavern is a two-story brick building that features Federal-style details, including fanlit entrances and a neoclassical Doric cornice. In 1989, a fire gutted the landmark, but Preservation North Carolina worked with local interested parties to stabilize the building for future restoration. Historic Preservation Agreements were placed on the property in 1992, and work began in restoring the tavern for use as a museum to honor Day and his remarkable story. In February 2024, Union Tavern was designated as a State Historic Site.

Preservation NC holds preservation covenants on a collection of Thomas Day–associated properties, including:

The Wilson-Winstead House, known as Melville, in the town of Milton was protected with our covenants in 2009. The two-story, brick house was built around 1830, with a blend of late Federal fanlit entrances and Greek Revival lintels with cornerblocks. Interior features are stamped as the products of Thomas Day. Its handsome Greek Revival front porch was carefully reconstructed in 2023, for which the project was recognized with a Gertrude S. Carraway Award from Preservation North Carolina.

To the east of Milton stands the Day-attributed Woodside property, a ca. 1825 brick Federal-style residence built by Caleb Richmond that was expanded and remodeled around 1855 with interior appointments in the style of Day. Woodside was meticulously restored and then protected by covenants in 2016.

South of Milton, in Yanceyville, is the Bartlett Yancey House, initially built by its namesake around 1810. A large addition was erected in 1856 by Yancey’s daughter, Ann, and her husband Thomas Womack, that is documented to Thomas Day. As such, it serves as one of only four structures that assist with the identification of other Thomas Day works through designs of mantels, newel posts, and molding profiles. The Bartlett Yancey House was PNC’s second protected property, with covenants recorded in 1978.

Bellamy Mansion, Wilmington

Preservation NC has owned and operated the Bellamy Mansion Museum of History and Design Arts since 1993. With the help of the Bellamy family, many scholars and volunteers along the way, we have extensively researched the site to learn and share every possible detail about the site. We encourage you to explore the Bellamy Mansion Museum website (and take a visit to Wilmington!) to learn more than we can possibly cover here.

Enslaved and free Black artisans built this urban compound between 1859 and 1861 for Dr. John D. Bellamy, who made his fortune from 115 enslaved workers spread across three counties. The opulent house signaled his wealth.

Rufus Bunnell, the young white supervising architect from New Jersey, kept a detailed diary during the construction of Bellamy Mansion, detailing the names and skills of the Black workforce. Many skilled enslaved artisans were hired for their construction skills, including master plasterer William B. Gould and carpenters Henry Taylor and Frederick Sadgwar. Free Black laborers and artisans were also hired, including members of the Howe family which encompassed four generations of builders.

The carpentry foreman was Elvin Artis, a free Black man. Artis owned several lots in Wilmington and his family resided in a home at the corner of 7th and Brunswick Streets for over 50 years. The city contracted Artis for projects throughout the 19th century. He was an active Republican in Wilmington, served as a juror at times, and operated a popular barbershop.

Through the skilled artisanry of free and enslaved workers such as Gould, Taylor, Sadgwar, and Artis, one of North Carolina’s grandest buildings was born. Bellamy Mansion features architectural elements unrivaled in our state at the time, including a main peripteral house featuring 25-foot wood columns, marble mantels, elaborate plasterwork, soaring windows, and a cupola. Importantly, the enslaved quarters on its grounds are among the most substantial in the state and among the best-preserved urban quarters in our nation. PNC completed a decade-long preservation of the Slave Quarters in 2014, ensuring visitors have a tangible and humbling interactive experience with our nation’s complicated past.

Matthewson House, Tarboro

George Mathewson was a brickmason active in Tarboro in the late 19th century. He was born into slavery, one of several children of white slaveholder John Mathewson and enslaved woman Rachel Pender.

Mathewson is credited with the erection of the Tarboro City Hall (along with African American carpenter Henry C. Cherry), and the Black Masonic Lodge in Tarboro. Census records from 1870 showed he had a carpenter’s apprentice, suggesting he was a multi-skilled craftsman with capabilities beyond masonry.

Mathewson was active in political affairs during Reconstruction, serving as a poll holder for Tarboro’s Third Ward and magistrate for Township No. 1 in Edgecombe County. His charming cottage in Tarboro served as a calling card to his expertise and attention to detail. It was likely built in the 1860s and is decorated with ornate lattice porch supports with curvilinear open brackets. The exuberant and distinctive porch trim can be found on other houses in Tarboro and likely serves as evidence of yet-undocumented examples of his work.

The Young Men’s Institute, Asheville

One of the most prominent African American builders of western North Carolina, James Vester Miller, started his own business at a young age. Born into slavery in Rutherford County, Miller moved with his family to Asheville when he was 10. Instead of going to school, he was fascinated with masonry and drawn to work in a brickyard.

He and his sons, whom he taught masonry skills, founded the Miller Construction Company. He experienced great success as a mason and real estate developer, building more than 25 rental houses for his workers (both white and Black) in the Emma community of Asheville, where he lived. Miller was committed to elevating his community, teaching masonry to young Black men without charge, and serving as an active community member. He often worked with Richard Sharp Smith, the white supervising architect whom he met while working on the Biltmore Estate. It was said that anything Smith designed, Miller built. Miller’s notable works include St. James A.M.E., Mount Zion Baptist, and Hopkins Chapel A.M.E. Zion Churches of Asheville.

Miller was one of the original incorporators and builders of The Young Men’s Institute, which provided services to the Black builders of Biltmore. This important building blends English vernacular building traditions such as pebbledash, red brick jambs, quoins, a pent roof, and exposed rafters.The building was recognized for its social history as a community resource for Black citizens.

PNC first protected the YMI Building in 1980, but due to legal restrictions on perpetual easements at the time, protection was scheduled to retire after 50 years. In 2025, PNC worked with the YMI Cultural Center to record a new permanent preservation easement that will ensure YMI remainsa tangible piece of Asheville’s Black history.